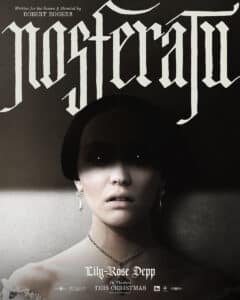

Nosferatu

In Germany, in Wisborg, in 1838, Thomas Hutter, newly married to the beautiful Ellen, is sent by the real estate agency he works for, to a remote residence in the Carpathians. As soon as he arrives in the region he is tormented by nightmares and witnesses barbaric local practices, furthermore a carriage mysteriously without a coachman arrives to take him to the castle of Count Orlock. The count demands that he sign a contract in an ancient and incomprehensible language. Only too late does Hutter discover its undead nature but, unable to oppose it, he takes refuge in his room. When the creature leaves the manor for the city, to get closer to Ellen with whom he has been obsessed since her adolescence, Hutter will risk his life to escape. In the meantime Orlock has unleashed a plague in Wisborg, which allows him to act undisturbed. He will give Ellen three days to give in to his deadly courtship.

At first glance it might seem that Ellen is the very cause of the arrival of the deadly presence in the city because, as we see in the prologue and as is later reiterated by Nosferatu himself, it was her desire that awakened the undead and attracted him to Wisburg. On the other hand, that desire is nothing but the resurfacing of social repression, of something that is constantly denied and punished. Even when Ellen shows obvious problems, Dr. Sievers, who is also a character with several positive traits, cannot help but recommend a tighter corset. What may then seem like an irreconcilable contradiction between Ellen’s nature as a mermaid and a saint, is in reality the mirror of a femininity that is positive and powerful in itself, enough to defeat the monster, but afflicted by the condition that society imposes. After all, this was also the theme in Eggers’ debut film, The Witch: even if there the ending went in a different direction, the source of a feminine danger was in the female condition.

If more examples were needed, it would be enough to say that even though Ellen had dreamed of the vampire during puberty, coming into contact with him, those nightmares were then brought back under control and the danger returns only when her husband decides to ignore her and leave her at home – it must be said that he is an affectionate man and will do so against his will, in turn a victim of social conditions that he tries to improve. There is also a very clear formal perspective in the film: desire is invincible when confined in the shadows, in the night, when therefore it is forced into a repressed sphere, while it is only by accepting it and bringing it to light that it ceases to be a danger. A reading that is reinforced by the character of Willem Dafoe, equivalent to Bram Stoker’s Van Helsing but bent towards a more visionary esotericism. He tells Ellen that in other times she would have been a priestess of Isis, a venerable figure for her spiritual gifts and not obliged to stay at home and give birth.

Formally, Eggers’ reinterpretation is impeccable, it takes up the image format of Murnau’s original and favors frontal shots, with a look into the camera, which he sometimes breaks with impetuous cuts and other times instead animates with elaborate movements. The partnership with the director of photography Jarin Blaschke continues, who works on shadows and on desaturated, ashen and enchanting images, and as in The Northman Eggers joins the young composer Robin Carolan, who signs a impetuous soundtrack like those of silent cinema. A perfect and artistically coherent package also for the costumes and the rich scenography, inhabited by actors of rare intensity: on the one hand Lily-Rose Depp who for certain incredible movements was guided by a choreographer of the Japanese Butoh dance, on the other Bill Skarsgård once again unrecognizable in his transformation – which also breaks away from the model of Dracula and also from the previous Nosferatu: he has no protruding teeth, neither incisors nor canines, and is instead a hardened corpse with exposed wounds but still with a moustache. Dafoe then plays with the usual contagious enthusiasm a character, as we said, different from the previous Van Helsing, so much so that his name is not Bulwer as in the original by Murnau, but Albin Eberhart von Franz in a double homage: to Albin Grau, producer and set designer of the original film and to the Jungian psychologist Marie-Louise von Franz, who worked on the archetypes of the fairy tale and was fascinated by alchemy.

Everything is flawless, with the only limitation of an extended duration, instead of the synthesis of the original, and with few surprises: apart from the novelty of the prologue, the film is exactly what you would expect if you know Eggers’ cinema.