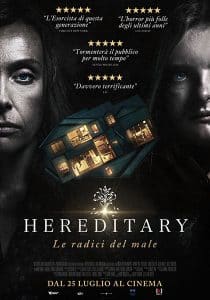

Hereditary

Ellen Graham dies together with her mysteries. While her daughter Anne elaborates the mourning of a complicated maternal figure, strange episodes occur in the Graham’s house, which seem to presage a tragic epilogue. All it takes is a slow and enveloping machine movement, between the sinister dioramas assembled by the protagonist Anne Graham to make us understand what we are going to meet with Hereditary. A distressing drama about the traumas of a family of rare dysfunctionality and an ambitious debut, which looks to the masters of the past to generate new shocks.

In this sense, the title is both twofold and evocative, referring so much to the Graham family’s evil roots and to the inevitable legacy of the Shining, the exorcist and Rosemary’s Baby who have gutted and remodeled our most unspeakable fears.

In a panorama that continues to hold horror in quantitative and qualitative terms, Ari Aster’s debut is at the antipodes of Blumhouse style Obligation or truth and their shameless exploitation and in the wake of works such as Eggers’ The Witch. That is to investigate the ancestral fears of man and how these are reflected in a contemporary that seems increasingly helpless towards them.

We were just saying dioramas, a new visual form of horror for mimesis – after fetishes or killer dolls – which is the key to a film that opens up to different interpretations, but with a single convergence. The will to understand the world and its madness through representation, even of what would seem “unrepresentable” (and therefore “not filmable”). And together the substantial defeat of this will, crushed by the weight of the consequences. The overturning between animate and inanimate, between manipulator and manipulated, is already in the incipit, and will follow in all Hereditary, with compulsive accumulation of horrifying, grotesque and sometimes oxymoric elements.