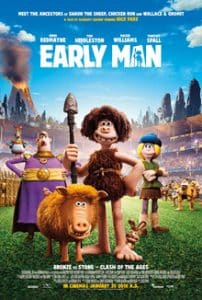

Early Man

The young Dug caveman lives in the forest in harmony with his tribe, anchored to the elementary life style of the Stone Age, until a group of warriors who have fully entered the Bronze Age hunts all (relatively more) primitive ones in the arid Badlands , subtracting the most fertile lands from them. But Dug does not resign and infiltrates the enemy’s territory, where he learns that the favorite game in the Bronze Age is … football. And because some paintings on rock stones reveal to his tribe that he had ancestors footballers, Dug decides to challenge his enemies to a game: if he wins he will get his land back, otherwise all his tribe will have to work in the mine for the winners.

After fleeing hens, Wallace and Gromit – The curse of the werewolf, Down the pipe and Shaun, life as a sheep, the English animation studios Aardman try their hand at a new story of redemption in claymation, ie shot in stop motion with figurines of play dough.

To distinguish Aardman is not only the animation technique but also the agile direction and the strong ironic vein that can only be defined as “English humor”. So even primitives are dotted with sarcastic jokes about England, the evolution of the species and the greed of certain rulers. There is also an implicit criticism of progress seen as positive tout court: despite the Bronze Age brings with it great innovations – from the wheel to the use of fire, from hunting and cooking utensils to metalworking ( plus some decidedly anticipatory inventions, such as money and the writing of newspapers) – the cavemen are the most gifted with an ancestral (it should be said) social sense, which is expressed in team building and living in harmony with nature. The authors also add a pro-racist spin: to teach Dug and his companions to play football is Ginna, a girl who has chosen for herself the role of striker but who is not allowed to play in the stadium as a girl, and to really dominate the Bronze civilization is not the conceited Lord Nooth but a wise and perspicacious queen as well as much less greedy and materialistic than the “first leader”.

The direction is as always very lively, not only because it must flow into a football match of great narrative tension, but also because it calls into question some cinematographic conventions: an example for everyone is the presentation of Giant Gosl, which initially appears normal size and then, thanks to a reversal of perspective, reveals (to us and the protagonists of history) all its enormity. The final game then makes an ironic reference to all the topos of the “noble game” football, from the simulated foul to the referee sold up to the “moviola” rigged.