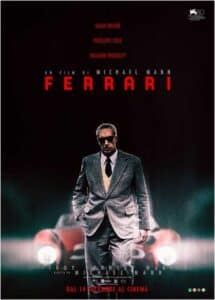

Ferrari

Modena, 1957. Twelve years after the end of the war, Enzo Ferrari, a former racing driver mourning the recent death of his son Dino, manages his car company with his wife Laura and lives in secret with his lover Lina, mother of illegitimate son Piero. Obsessed with the competitiveness of his cars in speed races, Enzo pushes his drivers to put their lives at risk in order to prevail, while the need to financially support the company forces him to renegotiate his collaboration with his wife. The Mille Miglia will offer the Ferrari man and entrepreneur the opportunity to make a change in their professional and private life.

Michael Mann worked for a long time on the figure of Ferrari, who in his hands becomes a Saturn capable of devouring his own children (the two natural ones and his own metal creations), master of himself and his obsessions only in the dimension of extreme speed .

At a certain point in Ferrari, which covers just one year in the life of the Modenese entrepreneur except for a couple of sporadic flashbacks and some inevitable shortcuts in the historical reconstruction, the protagonist played by Adam Driver tells the designer Sergio Scaglietti (Lino Musella) that his latest creation, the splendid Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa, has «an ass more beautiful than a statue of Canova»: it is one of the few moments in the film, in reality, in which the famous flaming red cars, «the flagship of Italian production » (as we hear the lawyer Agnelli say), are at the center of the scene, fully described and observed as heavy and metallic but irresistible and seductive objects.

For the rest, the biography long pursued by Mann and written by Troy Kennedy Martin (who worked from Brock Yates’ book ‘Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine’) favors family melodrama and the multifaceted portrait of a man separated from his own life and his own creatures. We don’t see engines in Ferrari, we almost never talk about engineering, the purely imaginative dimension of the Maranello reds is almost never exalted…

Almost ten years after Blackhat, with which Mann found bold and experimental images to represent the unrepresentable digital technology, the transition to a more classic story and the biography of a champion of twentieth-century capitalism, split between business and feelings, body and speed , space and time (as Ferrari explains to its drivers: two cars cannot occupy the same space in time, and therefore whoever is driving must brake or accept the possibility of death…), unfortunately generates an unresolved and off-centre film .

This is undoubtedly the fault of the production aspects of the operation: a not very high budget which lowers the formal care and quality of the digital images (but it must be said that fortunately, with Mann at the helm, the portrait of Italy in the 1950s never expires in postcard effect); the obligation to use almost always foreign interpreters for Italian characters, with the consequent effect of ridicule and estrangement in the use of English and sometimes (for no reason) of Italian; the alternation between the family world of Ferrari and the corporate world of racing and production, which generates a pedantic and didactic story, only at times saved from the effect of a television biopic by the directorial mastery of someone who knows how to find some significant moments (such as the final monologue of the betrayed wife Laura, in which Penelope Cruz finally manages to make the character forget the linguistic extraneousness).