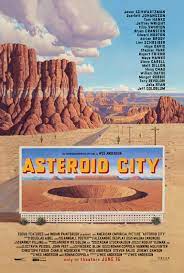

Asteroid City

Asteroid City, 1955. At a site in the Nevada desert, renowned for its crater after the impact of a giant asteroid, the fates of a war reporter in mourning for his wife, an actress he knows exists only in the gaze of others, a melancholic grandfather who tries to ‘reach’ his granddaughters, a scientist overwhelmed by events and a varied humanity lost in too large a space. During a convention of budding young scientists (the Junior Stargazer), who converged on the tourist town to present their inventions, an extraterrestrial ‘falls’ from the sky. The United States government, alarmed by the alien presence, places all those present in quarantine. Forced into captivity, they have to coexist patiently, forging bonds and crossing doors that lead to a black and white reality.

Like Simon Axler (“The Humiliation”), Wes Anderson has lost his magic. All the better, because that creative impotence becomes the magnificent subject of Asteroid City.

A film about the desert of our discontent that begins with a breakdown. A broken down car in the middle of nowhere, a cratered city, a huge hole with which the author, film and characters will have to come to terms and compose, (re)compose themselves.

Unlike the effervescent The French Dispatch, which saturated plans in an attempt to combat the absence of dramatic and thematic footholds, Asteroid City embodies the void. If Wes Anderson has always managed the miniature of large spaces (The Darjeeling Train, Moonrise Kingdom, Grand Budapest Hotel), this cartoonish desert is a space too large for him, impossible to govern. It is an alien ‘trick’ in three acts which confronts its heroes with inner emptiness to better reassert the power of stories.

Stories squared and cubed, because Asteroid City is a play narrated by Bryan Cranston and adapted for television by Adrien Brody. A black and white play that also becomes the color story of those who bring the story to life. Through a game of scenes and flashbacks, the fiction feeds on the life that awaits on the balcony and in a regal sequence with Margot Robbie, in which characters and actors merge (with) each other.

Stuck at Steve Carell’s service station and in the paranoid America of the 1950s, Anderson’s cinema put life on hold with its thousand characters, more consistent than the stellar army of The French Dispatch, which the decorative overload ended up devitalizing .