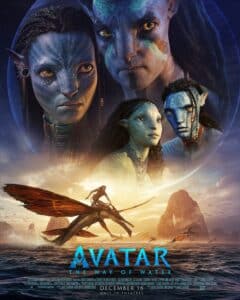

Avatar – The Way of Water

After the victory over the human invaders, the Na’vi have lived in peace. With them were some terrestrial scientists together with their avatars and a boy too young to be sent back to Earth. Named Spider and son of the late Colonel Quaritch, he grew up with the family of Jake Sully, who has three natural children: the eldest Neteyam, the rebel Lo’ak and the little Tuk. Furthermore Jake and Neytiri have adopted Kiri, daughter of the avatar of Augustine Grace and of unknown father, with a supernatural connection with Eywa, the great mother of Pandora. The Earth is in worse and worse conditions and Pandora could be a new home for humans, who return to the planet more warlike than ever, this time also with avatar soldiers – including a “new” Colonel Quaritch, i.e. a Na’vi body inhabited by a backup of his consciousness. He will inevitably seek revenge against Jake, who in the meantime has become the leader of the Na’vi rebels, and will force him to leave the forest to seek refuge with his family among the Metkayina, peaceful inhabitants of a large archipelago.

In spite of the many characters, the true protagonist of Avatar is indisputably Pandora, but are her enchanting beauties enough to keep up a film with a monstrous duration of over three hours?

Cameron goes to great lengths to recapture the first film’s sense of wonder and restore the magic of cinema once again. The vision of Avatar – La via dell’acqua, it must be said immediately, only makes sense in theaters. The director uses all currently existing technological means, from 3D to state-of-the-art CGI, from motion capture (also underwater for the first time) to the controversial HFR. Here lies the most interesting technical challenge, given that those who had attempted it before Cameron had failed: neither Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit, much less Ang Lee’s two HFR films (Billy Lynn – A Hero’s Day and Gemini Man) convinced the audience.

It is no coincidence that this technology was hardly mentioned in the promotional campaign, as if it were a taboo subject. To make it work, Cameron used it in a significantly different way than its predecessors: given that HFR projections are not modulable and show a greater number of frames per second (in this case 48) for the entire duration, the Canadian director has decided, for non-action scenes, to double the frames of footage, so as to show only the traditional 24. In this way, the HFR is applied or neutralized from shot to shot, even within the same scene, avoiding hence the annoying soap opera effect in the interior dialogues.

But it is the very nature of a largely virtual film such as Avatar that lends itself particularly well to this technique: for example, the fact that hand-to-hand combat takes place between digital creatures solves the problem of stuntmen, who are no longer credible when image hypersharpening is applied. Likewise, the more hi-tech scenes, such as the space ones, are something similar to the “cut-scenes” of a video game with the best computer graphics imaginable and will send the most demanding gamers into jujube broth. That said there is also an occasional downside: when large structures are framed, with no humans or animals around to give a sense of scale, they end up hopelessly looking like toy models, such as in a train crash at the beginning of the film.