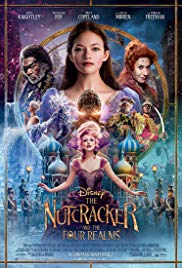

The Nutcracker and the Four Realms

Like every Christmas Eve, the Stahlbaum family meets in the big hall of the Drosselmeyer house to party. But it is a sad eve for Clara and her brothers, because their mother, Marie, has just died. Before going to the evening, the father delivers the gifts that his wife has left them: this is how Clara receives as a gift a strange casket, locked up. And it is looking for the key, stolen by a mouse, that will find itself in a magical country and, with the help of the Nutcracker Phillip, will have to fight to bring back the harmony between the four kingdoms that compose it.

Two forces move the world, it seems to say the script of Ashleigh Powell: one is a physical force, on which mechanics operates, and in a sense also the mechanics of the body in the ballet, the other is a psychological force, it is called courage , and it is necessary to leverage it when life becomes difficult.

To contain both forces is the character of Clara, who makes its appearance for the first time in this rewrite of the original story, almost a sequel; but, more generally, it is the film as a whole to capture also because it is constructed as a gear, a journey through different but equally faithful, visually, to the theme of mechanical movement, whether it is the papery of the pop-up or that of objects spring.

Of all the princesses or recent heroines of Disney movies, Clara calls to mind more than all the Alice of Tim Burton, a young commander struggling with creatures in the shapes and carnival dimensions, but behind the mystery of the key and the gears of the clock there is also the journey in the wonderful cinema of the origins of Hugo Cabret, there are visual suggestions come from the Chronicles of Narnia and others, very strong, from the Wizard of Oz. And yet it is not a cumbersome quotationism, that of Lo Schiacchianoci and the Four Kingdoms, but a way of voluntarily entering a certain imaginary, classic but moving: a repertoire that, with the addition of the right weight, can bring new film magic .