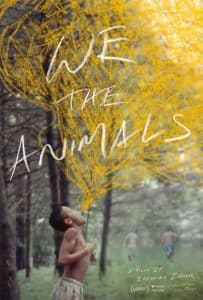

We the Animals

Based on a book by Justin Torres that comes from a real life experience, the film by the US Jeremiah Zagar features three Puerto Rican brothers Manny, Joel and Jonah, living in a backward area of the United States called Utica. The story is about their complicity and their relationship with their parents: an affection often interrupted by furious quarrels, by the abandonment and return of an impulsive and unhappy father, and with all the repercussions this has on the balance of family at home. The children make their way in their childhood, but Jonah compared to his brothers growing begins a personal journey that is detached from the ideal masculine incarnated by his father and pursues the definition of his sensitivity, opening up to what he feels. A path that promises to be more impervious – and more secluded – but certainly freer.

Zagar winner in 2009 of the Biografilm Festival with the documentary, as well as the first work, Into a Dream, after the excellent result obtained by the critics at the Sundance Film Festival presents at the 2018 edition of Biografilm his second feature fiction film. The film is the story of a memory and somehow tells us that we also remember through the media we came into contact with, we are influenced by it.

The director is linked to the memories of 35mm or 16mm videos, in Technicolor, while now everything is clean, clear, digital. We the Animals instead is shot in 16mm film, which with its thick grain gives the excellent photography a sense of material and warmth to the beautiful colors of dawns, sunsets or sunlight that filters through the windows and gently furrows the faces of children. This suggestive and enveloping light, together with the spreading lyricism and intimacy (the whispers, frequent recourse to close-ups) that pervade the story, as well as the free and sinuous machine movements, bring this film closer to the ethereal style of Terrence Malick. The feature is made with a mixed technique: live footage that alternates with animation sequences, in the style of shooting step one. That is, photocopied and repeated drawings on paper for about 6500 drawings. With the camera on the shoulder, Zagar often resumes in the middle of the scene, among the characters. There is a strong empathy, almost participation, empathy. The camera is always in the middle. He never loses sight of them. Indeed, it breaks the boundaries of cinematic diegesis and is grabbed by one of the children. Vitality and creativity are at the center of this story about the relationship between growth and suffering. Little Jonah is the main spokesperson: the art is often used by him as a vent, as a place to hide, the only moment in which to feel truly free. Children are surprisingly non-professional actors and scenes are often the result of improvisation, without written dialogues and entrusted to their irresistible spontaneity. Nature continually overpowers them, starting from the vegetation of the fields and the thick foliage of the trees that stand behind their heads, up to the presence of water, a very important element because associated with detachment from oneself and paradoxically also that of reconciliation with itself, moment of suspension par excellence. Swimming is a bit like flying. Zagar demonstrates an ability out of the ordinary in building a story so authentic and so full of life on childhood succeeding in a very delicate – but straight – to introduce the theme of discovery at an early age of their sexuality.