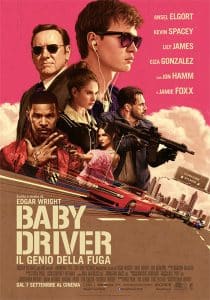

Baby Driver

Baby, so it is called, is a young man who drives a car is able to perform the most daring evolutions. This skill is exploited by Doc, a bourgeois-looking criminal, with whom he has an open account that must pay off. Baby must also take care of the disabled elderly who has made him grow up and is falling in love with the waitress of a fast food restaurant. What he would now like to do is detach himself from the continuous cycle of robberies that Doc orchestra.

Since the opening sequence, Edgar Wright proves to be absolutely aware of his potential.

It opens with a robbery and a reckless escape whose fate depends on Baby, an apparently autistic teenager who lives protected by the armor of music. A defense certainly needs because Doc (a Kevin Spacey fattened for the occasion) is extremely guarded, dangerous and vindictive. Unfortunately, Baby did not respect the old adage that invites us not to steal from the thieves’ house and is forced to drive the cars necessary for the robberies until they have extinguished a debt. But the music protects him from a reality that sees him at the same time active (driving) and passive when he is forced to a new business. Mixing sounds and voices from his daily life, he builds a soundtrack of life that helps him to move forward without forgetting the one to whom he owes (almost) everything. Which, not surprisingly, is deaf and dumb. So the screeching of the braking, the roar of the engines and the shots of a firearm find their own sound oasis at home and in its earphones.

Wright thus manages to work on a ‘other’ level compared to that of the basic crime story, offering us a refined essay on the possibilities of revisiting a genre. Ivi understood when he grafted the love story that contrasts the lucid madness of the character played by Jamie Foxx. With only one negative element: the repeated reappearance of the last rival of Baby that threatens to undermine the suspension of disbelief until then wisely conjured.