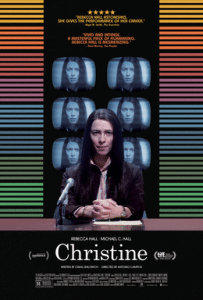

Christine

On July 15, 1974, Christine Chubbuck, a 29-year-old journalist at a Sarasota TV, Florida, after reading the news of a shootout in a local area, pulls out a gun from his purse under his desk and announces his attempted suicide. He shoots resolutely at the back of the neck. The film by Antonio Campos, written by Craig Shilowich, tells Christine’s latest times, his passion for work, the contrast with network decisions and his boss, the ghost of the depression he had already faced in the past That of Boston, and the premise that led him to stave the first direct suicide in the history of television journalism.

The Campos movie is not the only work dedicated to the Chubbuck case: this year is also Robert Greene’s documentary about the work done by actress Kate Lyn Shell to impersonate Christine in a movie that will not be made Never (Kate plays Christine), and it is well known that it was Sarasota’s reporter’s story to inspire the fierce satire of Lumet, Fifth Power. There is no real sarcasm, however, in Campy’s newyorkese biopic, but there is a mysterious self-irony of the protagonist, in his laugh to not cry a doctor who does not know he is still virgin, in doing what he does knowing “No one will look at it”: an oblique shade that breaks the dramatic register tout court and enriches a fascinating characterization of his own, which gives life and souls a Rebecca Hall in a state of grace.

Perfectly included in the 1970s painting of the seaside town, the editorial office and local television studios that the film recreates with great precision and suggestion, and perfectly credible in its dream of making it, going to Baltimore, making the jump of Network, And in the disappointment that follows, Christine of Hall stands out from the context without forcing any gesture or tone of voice, simply because of the strength of her presence and the complexity of her psychological portrait. To be sure of his talent, to the point of becoming lawful of what he does not get, and yet tireless in trying to perfect himself and in implementing new strategies, he knows how to make himself at first appointment with the spasified colleague, his mother and mother of his own mother.

With her endless intelligence and her low social empathy, Christine seems to look beyond the immediate present and her ridiculous bedroom, straight to us, viewers of the future, which she will always know and only the disturbing ghost. With her rushing to black, cutting off a life that coincides with work, the movie ends, and there is no sentimental tail that can bring emotion back to the levels when she was on stage.