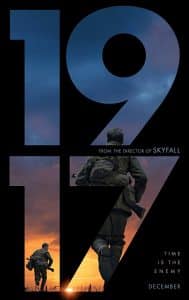

1917

April 6, 1917. Blake and Schofield, young British corporals, receive a suicide mission order: they will have to cross enemy lines and deliver a crucial message that could save the lives of 1600 men about to attack the German army. For Blake, the order to be transmitted takes on a personal character because his brother is part of those 1600 soldiers who must launch the offensive. Their path of glory ventures on rough terrain, no man’s land, empty trenches, uninhabited farms, gutted cities, to prevent a battle and to travel faster the time that separates them from 1918.

The Great War begins as a war of movement but ends up becoming a war of position. Unlike the Second World War, with its mobile fronts and its theaters of operations scattered all over the planet, which offer cinema raw material for the show, the First World War is a war of waiting, of impotence of men to overcome defensive barriers excavated by the enemy.

The challenge of Sam Mendes, who had already returned formal panache and narrative breath to James Bond (Skyfall, Specter), is to deactivate inertia and start the engine of a completely cinegenic conflict. A terribly long war with the lethal ankylosis of his fights and his abstruse reasons against the allegorical confrontation between good and evil of the Second World War.

The mission is high risk but Mendes overcomes obstacles, adapts the codes of the subsequent conflict to the First World War and launches two young soldiers in a race against time and into a visual torrent. Their odyssey is told ‘in real time’ with a single true-false sequence sequence: ‘from one tree to another’ without cuts or apparent connections, with the exception of discrete digital sutures and a single ellipse on black that allows you to pass from day to night.

The camera remains stubbornly glued to two unknown soldiers buried in the ghostly décor of the front. This is evidently an illusion, it will take our staff twenty-four hours to reach the end of their mission and 1917 lasts only two hours. The camera becomes the gaze of the viewer who can edit his film, zoom in, linger on a detail, but can never leave Blake and Schofield.

The spectator becomes the third companion, scrutinizes every danger, lowers his guard, becomes a vulnerable target, lives 1917 as a total immersion experience. The script of disarming simplicity, bringing an urgent message to the room unit in Écoust-Saint-Mein to prevent its massacre, is treated with stylistic prowess, an impressive technical tour de force, which accelerates emotions by capturing the daily ordeal without discounts lived at the front.